It’s amazing how congressional Republicans have been singularly unable, since winning the White House and both houses of Congress, to advance any major legislative priorities for their voters, but still quite able to advance legislation that most Republican voters would oppose — if they learned about it.

Republican leaders are sponsoring three bills that would expand the U.S. surveillance state under the guise of improving education and government efficiency. A grassroots opposition letter lists and summarizes the bills, the second of which passed the House last week:

- “The College Transparency Act (CTA) (H.R. 2434), which would overturn the Higher Education Act’s ban on a federal student unit-record system and establish a system of lifelong tracking of individuals by the federal government; [sponsored by Republican Rep. Paul Mitchell of Michigan]

- “The Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act (FEPA) (H.R. 4174), which would create a ‘unified evidence-building plan’ for the entire federal government – in essence, a national database containing data from every federal agency on every citizen; [sponsored by House Speaker Paul Ryan and Democratic Sen. Patty Murray] and

- “The Student Privacy Protection Act (H.R. 3157), which would amend the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), 20 USC § 1232g, without restoring the FERPA privacy protections that were gutted by regulatory fiat in 2012. [sponsored by Indiana GOP Rep. Todd Rokita]”

Government-expanding initiatives like these are not why voters have elected our current Congress or president. There is broad, bipartisan opposition to increased government surveillance of citizens, and for many excellent reasons. I list just a few of these below.

1. Personal Data Is Private Property

It has long been a core principle of American life that one of government’s main jobs is to secure citizens’ private property. People can’t just take our stuff without our explicit consent. Many state constitutions recognize this directly by stating that protecting private property is a fundamental purpose of government fit for a free people, and that their provisions are designed to secure it.

The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution is another prime example of our country’s design to restrain government and fellow citizens in this regard: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

This amendment has been used to protect citizens from wiretapping, police ransacking of cars and homes, and collection of personal information such as DNA and blood. Along the same lines, the data we generate as we live in a digital society belongs, rightly, to the individuals who generate it. Those incomprehensible user agreements you sign to get a Gmail or Facebook account acknowledge this by getting at least your technical consent to ransack and sell your data in exchange for the financially costless use of their services.

Government data collection and sharing, especially as expanded in these bills, transgresses against this social compact. Massive government databases already share huge amounts of personal information without disclosing this sharing to the citizens who own it. These bills would expand this infringement upon private property rights. Instead, Congress should do the opposite, and better secure our property rights by severely limiting the extent to which government agencies may collect and distribute our private information. My personal data is my property, not something for companies and governments to plunder for purposes I can’t control or even influence.

2. These Bills Kill Informed Consent, Which Kids Can’t Give

Another fundamental American right is to be ruled only by our consent. As the Declaration of Independence says, governments “deriv[e] their just powers from the consent of the governed.” We also socially recognize this principle as important when courts refuse, for example, to enforce contracts or agreements made under duress. Americans have a right to conduct their affairs according to their own free choices, not under coercion as in a mafia-style society.

Expanding government data collection and sharing transgresses this right because, again, already various agencies do not have to get explicit consent to distribute private information such as tax records, health conditions, test scores, and encounters with social services. These bills would expand their ability to share data without the explicit and specific consent of its owners.

Further, especially when we are talking education and health records, much of the data collection applies to minors, who in other arenas are legally prohibited from entering contracts because children are not mature enough to make good decisions. Children typically don’t have much life experience or neurological capacity to calculate the consequences of their actions, so they make poorer decisions than adults do.

It’s thus exploitation for people with no connection to a child and incentives against his interests to have the power to make decisions about his privacy and property. That’s why children in social services situations have court-appointed advocates. It’s also exploitation to make such decisions on the child’s behalf and without his legal guardians’ knowledge, let alone consent. Yet this is the situation our data-gathering is already in, and which Republicans plan to expand.

3. Informed Consent Is Key to Social Science Ethics

Some of the key purposes of this legislation is to secure and arrange data in order to conduct social science and other studies. According to psychological ethics and other social research protocols, I have a right to say whether I will be a test subject for someone’s research. These ethical considerations are even more strict for research conducted on children, since children are more vulnerable than adults are. These bills would further erode those important ethical standards by giving government more power to use citizens’ information for research conducted without their explicit consent, or in the case of children, even the capability of consent.

4. It’s Wrong to Exploit Americans Unable to Object

Other ethical standards are at play, especially the issue of power asymetry. Especially because our government is so large, it controls a great many things important to a great many people, including physical necessities such as food (SNAP), medical care (Medicaid, Medicare, drug and insurance regulations), housing (zoning laws, permits, Section 8 subsidies), and access to employment (permits, inspections, certifications). It also controls important social amenities such as education (both K-12 and college) and transportation (public transportation, licensing, and user fees). This gives it a huge power advantage over citizens, who in many cases are thus pressured to do things they dislike in order to have government-controlled goods.

This power differential is both implied and explicit. Many people cannot afford, for example, a private education for their children. Therefore if surveillance and manipulation as a result of that surveillance is bundled into public K-12 education and all college education thanks to Congress and the administrative state, these people will be coerced into accepting an exploitative situation that they would reject if they were truly free to choose.

It should go without saying that governments should not do this to their own citizens. This is a gross misuse of power that especially exploits those with the least political and financial resources.

5. Kids Do Stupid Things More Often

A main reason juvenile justice records are typically sealed is that a compassionate society wishes to protect citizens from lifelong consequences of young, foolish, and inexperienced actions. We recognize that young people are especially prone to stupidity, and we do not wish to punish them their entire lives for the immaturity they, by definition, cannot help.

Federal and state governments already transgress against this principle of justice by collecting sensitive data on young children in perpetuity, primarily through health and education records. The proposed bills will facilitate the increased sweep of such data into dossiers that will follow all Americans for life. Federal templates for data collection include entries, for example, for how many teeth a person has, school behavior records (including preschool), and whether some official thinks a student has ever “harassed” anyone.

Remember the kindergartener sent to detention for making a gun shape with his hand and saying “You’re dead”? On your record, kid. We’re watching you for other signs of “mental health issues” and “aggression.” Maybe it will play into your application for a gun license in 20 years. That may sound far-fetched until you learn that things like this are already happening.

As Cheri Kiesecker notes at Missouri Education Watchdog, “Recently, the Wall Street Journal reported that employers today are cherry-picking job applicants after hiring data brokers to determine who will be a risk for sick days, pregnancy, insurance costs.” Imagine how you would feel if your company knew you were pregnant before you decided to share that news because it was tracking your birth control purchases and searches inside their health insurance app. Again, it sounds crazy, but it’s right there in the Wall Street Journal. Federal college databases already include students’ child support payment history, net worth, retirement savings, parents’ Social Security numbers, number of siblings, parents’ child support payments, and more.

Michelle Malkin has documented how one data-tracking system used by several states records “information about [public preschoolers’] trips to the bathroom, his hand-washing habits, and his ability to pull up his pants.” I can hardly wait to see what potty training gets correlated with in these government algorithms, given its already-fraught history of psychological abuse.

6. The Bigger the Database, the Bigger the Bait

This one is simple. Data is bait because it’s a commodity. Where do you think Facebook gets its money?Trafficking customer data. The better the data, the more complete the profiles, the more it’s worth, both in financial and intel terms. The more it’s worth, the more hackers, corporate interests, and government agencies are going to want access to it. It’s kind of like creating the One Ring to Rule them All. Do that, and everyone wants it, most especially the people who have the worst plans for how to use it. So don’t do it.

7. Federal Data Security Is Awful

As the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy points out:

In recent months it has become clear that data held by post-secondary institutions and government agencies are under increased threat of breaches and cyberattacks. Even our “best protected” national data has been breached, including the hacking in recent years of the National Security Agency (NSA), Department of Defense (DoD), the Office of Personnel and Management (OPM), and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Specifically, the U.S. Department of Education was found to have weaknesses in four out of five security categories according to a 2015 security audit by the Inspector General’s Office.

Said Rachael Stickland, co-chair of the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy: ‘It’s inconceivable that Congress should entertain legislation that would increase federal collection of personal student data at a time when they have demonstrably proven they are unable to protect what data they already hold.’

8. Big Data Is Prone to Prejudice and Political Manipulation

Things that sound innocuous, such as birth weight (another entry in federal databases), in a Big Data world can be used as predictive modeling that research has found is likely to compound prejudice. Low birthweight is correlated with lower intelligence, for example, poorer health, and poorer nutrition. It is not too far-fetched to assume that once these data dossiers exist, at the very least insurance and mortgage companies will demand access to them for their actuarial calculations.

Not only is this in itself sketchy, the resulting backlash is likely to produce unintended consequences such as we saw in the 2008 financial crisis. The entire world economy tanked because of mortgages governments forced banks to issue to people who were bad bets but part of politically protected groups. Who knows what the unintended consequences might be of expanded opportunities for class warfare.

9. No Research or Experience Justifies Sweeping Data Collection on Citizens

Myriad high-quality public, private, charter, and home schools have proven government surveillance is utterly needless to produce self-governing, contributing adult citizens. Fifty years of increasing school data collection and using it to manipulate citizens’ behavior have not proven competitive to these data-free and data-secure alternatives. It has mainly produced a lot of wasted time and taxpayer money, plus a bit of research, most of it useless, that federal overlords typically ignore or pervert for political ends.

Electronic medial records are already their own massive boondoggle. Although medical research has shown better results, even though it is also rife with waste, fraud, and abuse, it is of an entirely different nature than sociological research, citizen surveillance, and economic manipulation of the kind being contemplated with these plans. We are not talking about running very specific, double-blind studies of some medical treatment. We’re talking vacuuming every datapoint bureaucrats can get their hands on, without specific consent, for vague purposes and limitless storage. It would be like if medical researchers perpetually conducted experiments of their choosing without subjects’ knowledge or consent and used the results to alter patients’ treatment opportunities and conditions also without their knowledge or consent. That would be insane, you say. Exactly.

We as yet have no evidence that national databases that follow individual citizens around for life will significantly improve on America’s historic successes with securing citizens’ freedom to manage their own affairs in free association with other citizens. The freedom to make one’s own decisions based on personal information and values, and control one’s own property and destiny, is a priceless treasure that U.S. citizens should not be forced to trade for K-12 public schooling, a college degree, or just simply being an American citizen. The cost of this trade is too high and the benefits too obscure and unproven.

10. Government Doesn’t Use Well the Data It Already Has

Data surveillance advocates, such as Tiffany Jones of The Education Trust, who testified to Congress on one of these bills, argue that “Before disaggregation of data was required in K-12, we knew anecdotally that schools were not educating all groups of students well. But we did not know just how significant the

inequities were, and we didn’t know which schools were making progress and which weren’t. That, unfortunately, is where we still are in higher education — especially in regard to low-income students.”

She’s referring to No Child Left Behind, which required K-12 public schools to publish information about specific “subgroups,” such as children labeled low-income, a racial minority, or special-needs. NCLB became law 16 years ago. In that time we have indeed gotten more details about the state of education for these children, which is abysmal. We knew that before the data collection, however, and did nothing about it.

Federal bureaucrats may have not been able to draw up an Excel sheet of all the low-performing schools in the country, but that doesn’t mean “we didn’t know” which schools were underperforming. Almost any person in those schools’ communities could have told you that. What Jones means by “we” is the people she assumes should run schools, which are obviously not local citizens paying local taxes and enrolling their kids in local schools. It’s people like her, who for some reason assume a divine right to tell the rest of us how we should run our lives.

After collecting NCLB data and much more for 15-plus years, “we know” more but still are doing nothing effective to address what it depicts. It is instead being used to make arguments like this, for increasing federal micromanagement despite a 50-year track record of that harming education quality.

11. Data Collection Is Not About Improving Education, But Increasing Federal Control

The real purpose of collecting data, as No Child Left Behind and its predecessors and children have proven, is to give federal bureaucrats excuses to meddle in local affairs and individual choices. This is what they have done with the information they’ve generated so far, and this is what they plan to do with more of it.

Data-driven pseudo-knowledge gives bureaucrats political power, which they have so far used to produce no significant gains from any federal education program in more than 50 years of increasing strangulation. Since federal surveillance for the purpose of micromanagement has been proven not only to not advance these important social imperative, but to actively retard them, we should obviously reduce federal data surveillance rather than increase it.

12. Americans Are Citizens, Not Cattle Or Widgets

One of the major intents of collecting education information is to integrate it into economic planning. You read that right: Republicans are helping accelerate the United States towards a planned economy, despite its well-known and horrific failures. (Shocker.) Political scientists call that “communism,” kids. The explicit goal is to have government decide what life choices citizens must — or will be manipulated to — make based on bureaucrats’ beliefs.

Democrats tend to like this because most Democrats support unlimited government, or socialism. Republicans (and Democrats) tend to like it because they tend towards fascism, or private associations that all must get government approval, which allows bureaucrats to control society. These are both two different flavors of a collectivist welfare state, and the existence of America’s welfare state provides the main pretext for this data control because government transfer payments grease the hinges for government surveillance.

But both of these views of American citizenship are wrong, because they treat citizens not as individuals with the right to govern their own affairs, but wards of the state that the protected class may mold and subjugate as it pleases. In other countries, people’s rights are granted to them by the state. What the state gives, it can take away, and often does. In the United States, however, citizens’ natural rights are inherent, and the organic documents that created this country describe them as “inalienable” and bestowed by God.

In the United States, government is supposed to represent and function at the behest of the people, and solely for the protection of our few, enumerated, natural rights. Our government is “of the people, by the people, for the people.” We are the sovereigns, and government functions at our pleasure. It is supposed to function by our consent and be restrained by invoilable laws and principles that restrain bureaucrats’ plans for our lives. These include the natural rights to life, liberty, and property. National surveillance systems violate all of these.

As attorney Jane Robbins points out, “In a free society, the government is subordinate to the citizen. If it wants to use his data for something he didn’t agree to, it should first obtain his consent. [The Ryan-Murray bill] operates according to the contrary principle – that government is entitled to do whatever it wants with a citizen’s data and shouldn’t be hindered by his objection.”

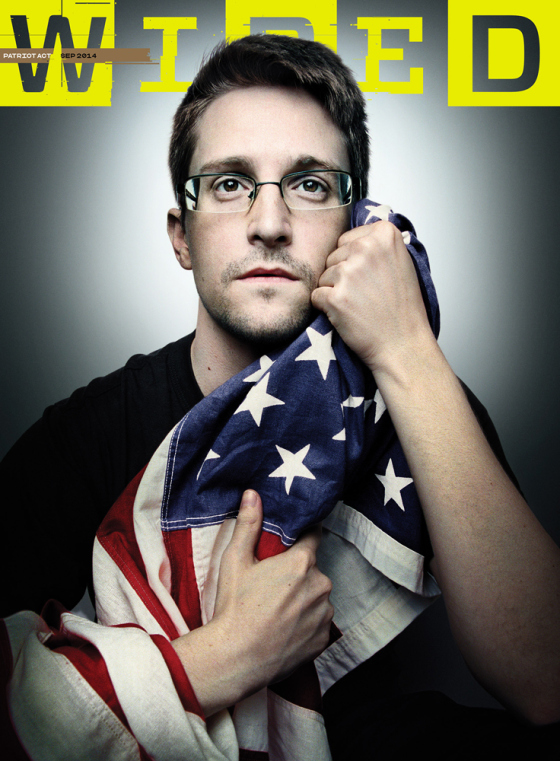

If Snowden was dismayed by the magnitude of NSA abuses, he could have exposed them without indiscriminately handing over … well, handing over what?

If Snowden was dismayed by the magnitude of NSA abuses, he could have exposed them without indiscriminately handing over … well, handing over what?